Did you know that autism has a high prevalence in people who are partially sighted/registered as blind? How about how, for many autistics, a lack of synchronicity between the eyes leads us to view the world as two overlapping images?

Did you also know that for many autists our place on the spectrum can dictate whether we have eyes akin to a kaleidoscope or ‘super-vision’ that rivals a hawk?

Yes, when it comes to autism, eyes and all things vision, autistic sight is just as diverse as the spectrum itself, but how (and why) do these differences present in the first place, and is there a reason why these differences can seem so extreme?

Physical Differences in Autistic Eyesight

So let’s just say it as it is, autistic people have a bad relationship when it comes to our senses; In some circumstances they’re so highly tuned that they overload and cause us to meltdown whilst, on other days, they don’t even show up (probably distracted by their latest obsession).

To that extent, it’s little wonder why many will disregard the issues that autistic people can face with their eyes; all too often putting these problems down as just another biproduct of our rather sensitive senses. However, if you’ll pardon the pun, there is more here than meets the eye.

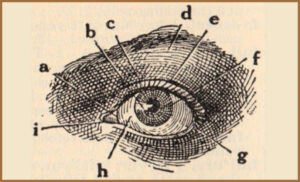

I say this because, unlike our other senses: taste, smell, hearing and touch, sight has many rather special characteristics when it comes to autism in that, despite autism often being considered a solely neurological ‘disorder’, its impact on vision has many physical identifiers, with some 52% of autistic people having some kind of ocular abnormality, which is significantly higher than the general population (3%-8%). This 52% includes:

- 7% with anisometropia (where eyes have varying refractive powers)

- 11% with amblyopia (A lazy eye)

- 27% with significant refractive error (where the shape of an eye prevents light from bending correctly)

- 41% with strabismus (cross eyed)

(according to a 2013 journal titled Ocular Manifestations of Autism in Ophthalmology)

Additionally, whilst on the easier side of affliction, it is said that autistic people are also 1.6 times more likely to experience having irritated/itchy eyes, there conversely exists an extreme affliction beyond deficits, wherein a growing body of research is finding somewhat frightening links between being autistic and temporary/permanent loss of sight.

Yes, these are the findings which state that anywhere between 17%-50% of those registered as blind are also on the spectrum – a recent discovery which has been credited to everything from a lack of development in the superior colliculus (a part of the brain responsible for reading emotions and processing what the retina sees) to mere coincidence (yes, that’s really some people’s best explanation).

But, hold on, let’s just quickly pull back before we fully submerge ourselves in the murky waters of speculation. As, whilst there exists a whole range of vague theories regarding autism and its impact on physical sight, this is still an undeveloped area of research that offers little to no clarification. Thankfully, the same can’t be said for autism’s impact on sight’s neurological links, a place which makes the spectrum look far less like a sight robbing highway man and far more, well, ‘super’.

Super-Vision and Neurological Differences in Autistic Sight

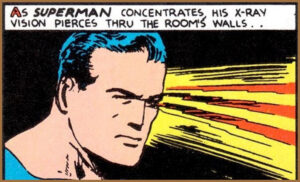

We’ve all heard the stories of autistic people whose eyesight puts a very literal spin on the phrase ‘autistic people see the world differently; they’re the legends who supposedly could spot Wally/Waldo, even if he was trained by a chameleon and wearing a ghillie suit. But, is it true that some autistic people really have super-vision?

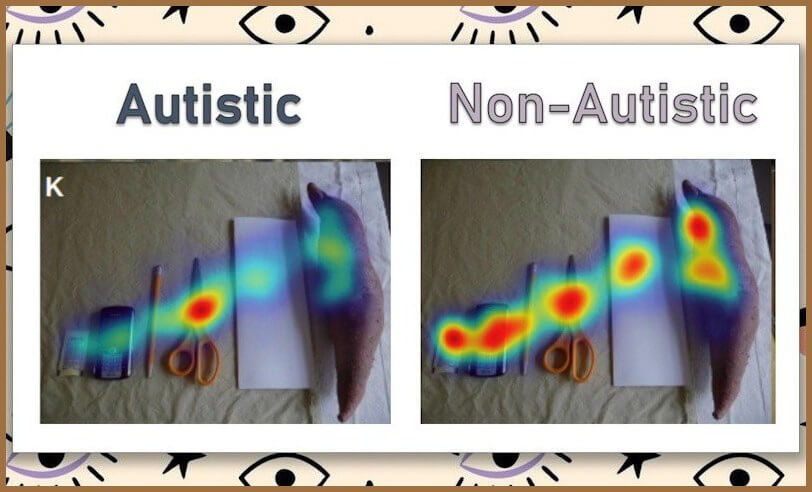

Well, as with everything in autism, the answer is a little more complicated than a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’, as while autistic people are capable of seeing things most will not, this is actually more down to our brain’s ability to more thoroughly process every aspect of an image – as opposed to the non-autistic brain, which can get lost creating a story around a singular detail.

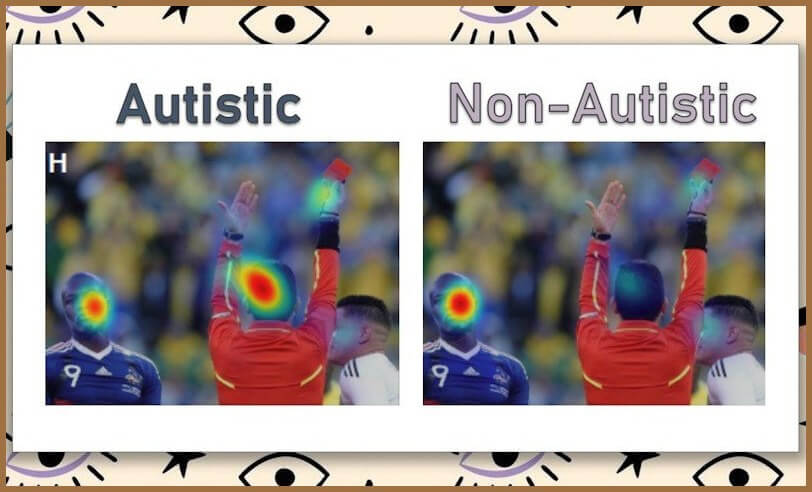

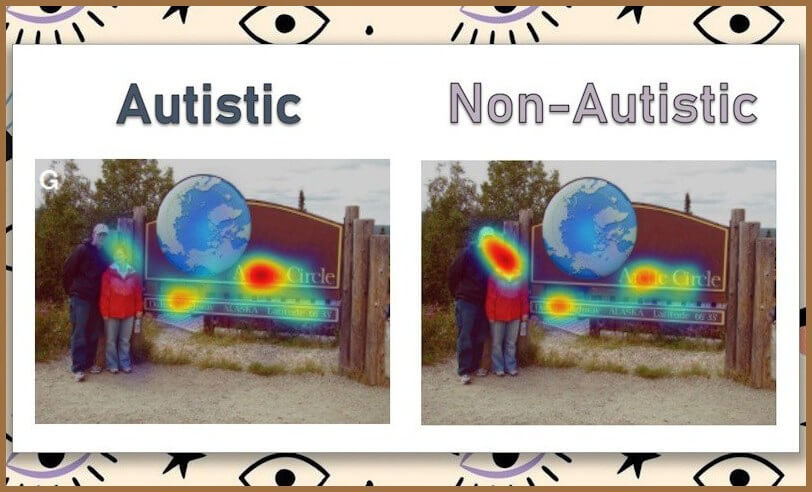

For example, when a non-autistic person enters a room or sees a new image, their eyes will first be drawn to something that is ‘visually salient’ i.e. sticking out. Following this, they will then try to use whatever is close by to make sense of that, essentially creating a snowball of understanding from one limited detail.

Of course, I’m not here to criticise what is right or wrong in this. However, in taking this path, the non-autistic brain often loses sight of anything which isn’t relevant to that which has been deemed the apple of their eye, leading to vision being an insular event with one and one focal point alone.

On the other hand, autistic people are all about patterns and learning the minutiae of how things fit together. So this means that when we walk into a room or are presented with an image, our brains won’t settle until we have categorized everything in sight; usually starting from an unbiased central point and working our way out (all the while avoiding faces or sights that contain a lot of surface-level uncertainty– click here for an explanation of why).

Put simply, this means that autistic people may have the same eyesight as non-autistic people, but by using what’s really ‘super’ about us: our brains, we learn to use the information contained in these sights in a much more optimal way, something which can clearly amaze those who are used to using there intellect and eyesight to create a granular story around one lone thing.

Using eye-tracking software, the below images taken from a recent study into autism and eyesight, demonstrate these differences:

That’s not to say that all non-physical autistic traits are a win for the spectrum though, as there is also a growing body of research surrounding the complications our brain can cause when trying to process the world around us – ranging from the obvious ‘autistic overload’ to newer discoveries like binocular rivalry in autistic vision (an issue which occurs as the result of autistic people gathering to much visual information, too quickly for us to process it – leading to us hold two misaligned images at once; what we are seeing and what we are trying to absorb).

However, even these are only minor setbacks; tiny hurdles which, if taught to be controlled, could be used to help our community excel. For this reason, you would like to think there has been significant headway in understanding the relationship between autism and sight but, alas, the truth highlights one of the more modern challenges our community faces.

Why More Needs to Be Done to Understand Autistic Sight

Autism clearly plays a big role in a person’s sight, so it’s infuriating to see that we still have such a low understanding of the exact way this manifests. This isn’t just because it makes for deeply unsatisfying conclusions to blogs discussing the matter though, but it’s also because of the incredible damage it does to our community – and the potential it holds back.

In particular, if everything put forward and theorised today is in fact deemed to be true, then it’s not too much of a stretch to say that autism’s impact on sight could be classified as a hallmark of the condition.

Now, that may not seem like much at this moment in time, yet, if we were to entertain this idea, it could easily lead to better eye support for autist from diagnosis. Similarly, more evidence on how autistic people process sight could also provide those seeking to promote autistic talent with sure-fire examples of how our unique perspective can overshadow non-autistics in certain settings.

That all sounds great right? Well, it doesn’t end there either as, if we do consider that autism can have a physical impact on the eyes, then it would further make for faster diagnosis times as, believe me, autism would be a LOT easier to spot if we had physical symptoms aligned to it, as opposed to a vague list of ever-changing criteria.

Unfortunately, this dream couldn’t be further from the truth at present as, not only does a lack of professional interest in this area stifle any chance of advancement, but, due to the low/virtually non-existent awareness of what we do have, many autists are having even the most basic support denied them.

This paints a particularly grim picture when you consider those in the community who are also partially sighted/ registered as blind, as all too often autism is under-reported and underdiagnosed in these areas, where professionals are misreading autistic indicators such as a literal mind – in the belief that those without sight have most of their understanding taken from physical interactions so, of course, they would think this way.

Given how much we still have to know about the neurology of autism, it seems unlikely that this landscape will be changing anytime soon. However, this doesn’t mean that I believe that such a day will never arrive.

Until then though, raising awareness of the things we do know is certainly the way forward; all the while hoping that someday, someone with the ability to make a difference will see the demand and suddenly have their eyes opened to the possibilities – so keep your eyes peeled for that!

Carry on the Conversation:

Did you know that autism and sight problems could be linked? Is there any information featured in today’s post which you would like to learn more about? Let me know in the comments below. And, if you want to learn more about how autism can alter over time, why not check out this article: Autism & Ageing: Does Autism Get ‘Better’ or ‘Worse’ With Age?

As always, I can also be found on Twitter @AutismRevised, on Instagram and via my email: AutisticandUnapologetic@gmail.com.

If you like what you have seen on the site today, then show your support by liking the Autistic & Unapologetic Facebook page. Also, don’t forget to sign up to the Autistic & Unapologetic newsletter (found on the sidebar on laptops and underneath if you are reading this via mobile) where I share weekly updates as well as a fascinating fact I have found throughout the week.

Thank you for reading and I will see you next time for more thoughts from across the spectrum.