In the world of autism, Alan Turing is somewhat of an inspiration. I mean, how often is it that our community can call dibs on someone who secured a victory within a war AND how often can it be said being autistic played a pivotal part in this outcome – you know, besides with Albert Einstein, Thomas Jefferson and most of the characters from the Underdogs series?

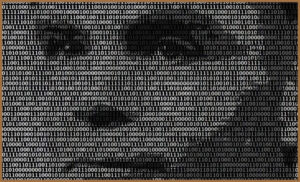

Nevertheless, while we may spend many a day celebrating Alan Turing as an autistic war hero, there is many a fabrication of fact surrounding Turing which, when considered, brings his spectrum citizenship into question – but does this mean that Alan Turing the autistic war hero was not quite so autistic after all? And why, on the month of his introduction onto the UK £50 note, does any of this matter to the autistic community at large?

What Alan Turing Was Really Like (Aka Everything ‘The Imitation Game’ Gets Wrong):

Turing once famously said, “It is not possible to produce a set of rules to describe what a man should do in every conceivable set of circumstances”. However, if you’re a screenwriter setting out to write a story depicting a historical figure, I’d assume that the very least you could do is capture a personality that even closely resembles your subject.

This, however, was not the case in 2014 Alan Turing biopic The Imitation Game *something I wanted to bring up right away as, often, when it comes to the idea of Turing’s supposed autism, it’s his depiction in the film which is the cause*.

Of course, while The Imitation Game does get it right that Turing was somewhat of a socially challenged intellect, Benedict Cumberbatch (who plays Turing in the Imitation Game) makes Turing seem arrogant and apathetic (or in other words, everything we have come to expect from a Hollywood depiction of autism).

In truth though, this is mostly make-believe hogwash as, despite being somewhat shy, those who got to know Turing had nothing but high praise for the man, stating:

- He was ‘charming’

- He was ‘cheerful’

- He was ‘stimulating’

- He was very ‘friendly’

- He was ‘warming’

- He was ‘Playful’

- He had ‘a boyish enthusiasm’

- He had ‘a great sense of humour’

- He had ‘a strong sense of justice’

- He had ‘a fantastic ‘sense of smell’ (okay, so I made that last one up, but I really wanted to find a third ‘sense of’ descriptor)

Most damning of all was that Turing was also incredibly honest about who he was at a time when being true to yourself could make life very hard. For example, while it’s no secret that Alan Turing was a homosexual (at a time when being so was illegal), back when Turing was alive his sexuality wasn’t much of a secret either -with him bravely opening up to his friends (and fiancée) on many occasions.

Of course, I could go on all-day about how large an opportunity has been missed by not celebrating the confidence Turing had in his identity (instead of viewing him solely as a tragedy of his circumstance), but now probably isn’t the time or place. So, before I get lost in that direction let’s move on to what this means for Turing’s place on the spectrum.

Was Alan Turing Autistic?

Although, many of the autistic traits which have been associated with Alan Turing are largely fictitious, there is still good reason to believe that Alan Turing was indeed autistic. This is evident when Turing is analysed alongside the autism diagnosis criteria from the most up to date diagnostic texts (the DSM-5 and upcoming ICD-11) where, in retrospect, it’s easy to point out evidential traits which pair his behaviours to the condition. For example:

Evidence of Social Communicational Challenges:

Throughout the history of mankind, it is far from uncommon to find that people of brilliant technical ability want to be left to their own devices. Yet, for Turing (and many other autistic people), this likely wasn’t a choice.

This is because, while Turing was often found in isolation, many reports state that this was involuntary, wherein despite being of ‘good nature’, he constantly grappled with understanding social norms and subsequently struggled to create solid relationships.

As one of his former acquaintances points out:

‘[Turing] craved affection and company, but never seemed to quite fit in’

And that:

‘He was the sort of man who, usually unintentionally, ruffled people’s feathers’

This one thing perhaps bothered Turing most, as he was reported as being very self-aware of the issues he had in social communication (which is partly the reason he wouldn’t take full leadership on his projects) but finding a solution to this issue was one problem he could never solve.

Evidence of Repetitive/Restrictive and Obsessive Interests:

It’s hard to know where to start when it comes to Turing’s repetitive, restrictive and obsessive behaviours, as there are so many to choose from! We could go big, like with his love for deciphering and decrypting code or, we could go for the small (yet no less important) traits, like how he had to have an apple at the end of every day.

Personally, I don’t think it matters where you start (as it really does appear everywhere you look), but for the most clear-cut evidence of an autistic compulsion in Alan Turing, I would point to Turing’s love of running.

This is because, whilst Turing did have many an obsession in his life (including, bizarrely, fortune reading), Turing’s running unquestionably fits the profile for autistic behaviour – as he often said that he ran with no purpose, not for health, not for victory, just because. That’s not to say he didn’t have a purpose though, as when pressed by those closest to him, Turing would on occasion state that he ran to make his brain quiet – a textbook example of autistic stimming.

Stimming: Repetitive self-stimulating behaviour often involuntarily used by autistic people to regulate emotion.

But does an inability to connect immediately make someone autistic, or could Turing have just been a little awkward? Similarly, does the need to blow off steam from a very demanding position indicate that Turing had spectrum identity or was running no different to switching on Netflix and switching off after a long day?

While, for Turing, I would be inclined to say ‘Yes’ (as all the evidence really does stack up), the challenge here isn’t that we know too little about Turing to make an affirmative decision, but that our understanding of autism is still so new and unclear that retroactively applying it can only do so much or, as a similar article on Medium states:

‘Attempts to diagnose Turing arguably reveal more about our current fuzzy concepts of autism than they do about Turing the man. And they make plain why we’re still a long way from understanding the enigma that is autism.’

Why Does Alan Turing’s Autistic Identity Matter?

So why is it important that we know whether or not Alan Turing was autistic? Well, in truth, it’s not. Sure, Alan Turing being autistic may have been vital when his obsessive and unconventional thinking led him to developments but, for all the good Turing’s autistic behaviours did him in life, a post-diagnosis has since been used to paint his public image in a manner that:

A) Does his true essence no justice

B) Insults the autistic community; as though the idea that an autistic genius can be social and empathetic is a myth.

What I find most concerning about this is that, due to how confidential his actions were during the war, Turing’s contributions to history have already once been cast into historical obscurity (up to and including after his passing). So, it seems all the more tragic that now, when we are able to fully realise the impact he has in our lives, we remember him inauthentically or we choose not to remember Turing, the man, at all (discussing his actions but rarely his real personality).

Don’t get me wrong, I love the fact that our community can say that we have an autistic war hero (I mean it just sounds great doesn’t it ‘autistic war hero’), but that doesn’t mean we should use autism to pigeon hold who he was when, instead, we should use it to show all that someone with autism can be.

Nevertheless, if this is how you continue to see the man, then by all means let his actions inspire you but, remember, whether you choose to see Alan Turing as an icon of autism, LGBT+ or for all of technology, honour his memory by recognising the person behind the achievement and let his true story show how the potential to create is not founded in isolated characteristics.

Carry on the Conversation:

Do you think it’s important for the autistic community to post diagnose history’s greatest figures (where relevant)? Let me know in the comments below. And, if you would like to read about another historical icon who is almost certainly on the autistic spectrum, then check out this article Why Santa Is Autistic (And Why It Matters).

As always, I can also be found on Twitter @AutismRevised, on Instagram and via my email: AutisticandUnapologetic@gmail.com.

If you like what you have seen on the site today, then show your support by liking the Autistic & Unapologetic Facebook page. Also, don’t forget to sign up to the Autistic & Unapologetic newsletter (found on the sidebar on laptops and underneath if you are reading this via mobile) where I share weekly updates as well as a fascinating fact I have found throughout the week.

Thank you for reading and I will see you next time for more thoughts from across the spectrum.